The Origins of the American Pastime

Baseball is America’s National Pastime.

Families in every state of this nation have enjoyed playing some version of baseball for well over a century.

Why is baseball our National Pastime? What are the origins of the sport?

Before the twentieth century, every region in the United States had their own version of “baseball” that was played according to the local rules. Additionally, every region referred to their game by a different name.

In New York State and the Great Lakes Region, their respective versions of bat-and-ball were referred to as “Base Ball,” or “The Game of the Bases.” In New England, “Base Ball” and “Round Ball” were used interchangeably. In Pennsylvania, Ohio, and in the South, the term “Town Ball” was used.

Even when the name of the game was the same, neighboring regions played according to different rules. The town ball of Philadelphia, for example, was a completely different game than that of Cincinnati.

In New York and Massachusetts, where in both places the game was referred to as “Base Ball,” Massachusetts had their version, whereas New York had their own. Once interstate competitions became more common, in order to differentiate between the two games, base ball in New York came to be known as “The New York Game,” and in Massachusetts, “The Massachusetts Game.”

The New York Game is essentially what we now refer to as baseball. This is the game that eventually won out as The National Pastime.

The Massachusetts Game, however, is almost completely unheard of in our nation today, except among baseball historians, or in the various vintage base ball communities that are springing up nationally right now at a feverish rate.

Why is it that The New York Game came to win out over The Massachusetts Game as our National Pastime?

Most likely there is more than one answer to this question.

The first reason that the New York version won out is that the New York ball players were superior to those of any other state. They would win almost any contest that took place between them and the others, regardless of which version of ball was being played. This gave them a reputation of being the “experts” at The Game of The Bases. This clearly went a long way in propelling their version into becoming our national sport.

A second reason was marketing. The members of the Knickerbockers Base Ball Club (The team from New York) were not only great ball players, but were also exceptional ambassadors of their game. They were the first ball club in this nation to codify for themselves their version of the game in written form. Once this was done, the other clubs found themselves scrambling to keep up.

We here at Twenty-First Century Townball believe that there was a third and just as important reason as the other two as to why baseball came to dominate as our national sport over all other versions of base ball in the late nineteenth century.

It comes down to mathematics.

Baseball is perfect mathematically in all aspects.

First, the field is a square, one of the most basic and beautiful shapes of geometry.

Second, almost every part of the game is broken down to the number three.

The bases are ninety feet apart (thirty times three), the pitcher is sixty feet, six inches from the batter (twice thirty feet three inches), there are nine innings (three sets of three), and each inning consists of six outs (one set of three for each team). There are three strikes for an out, and there are nine players per side (again, three sets of three). Even the World Series was originally a nine-game series.

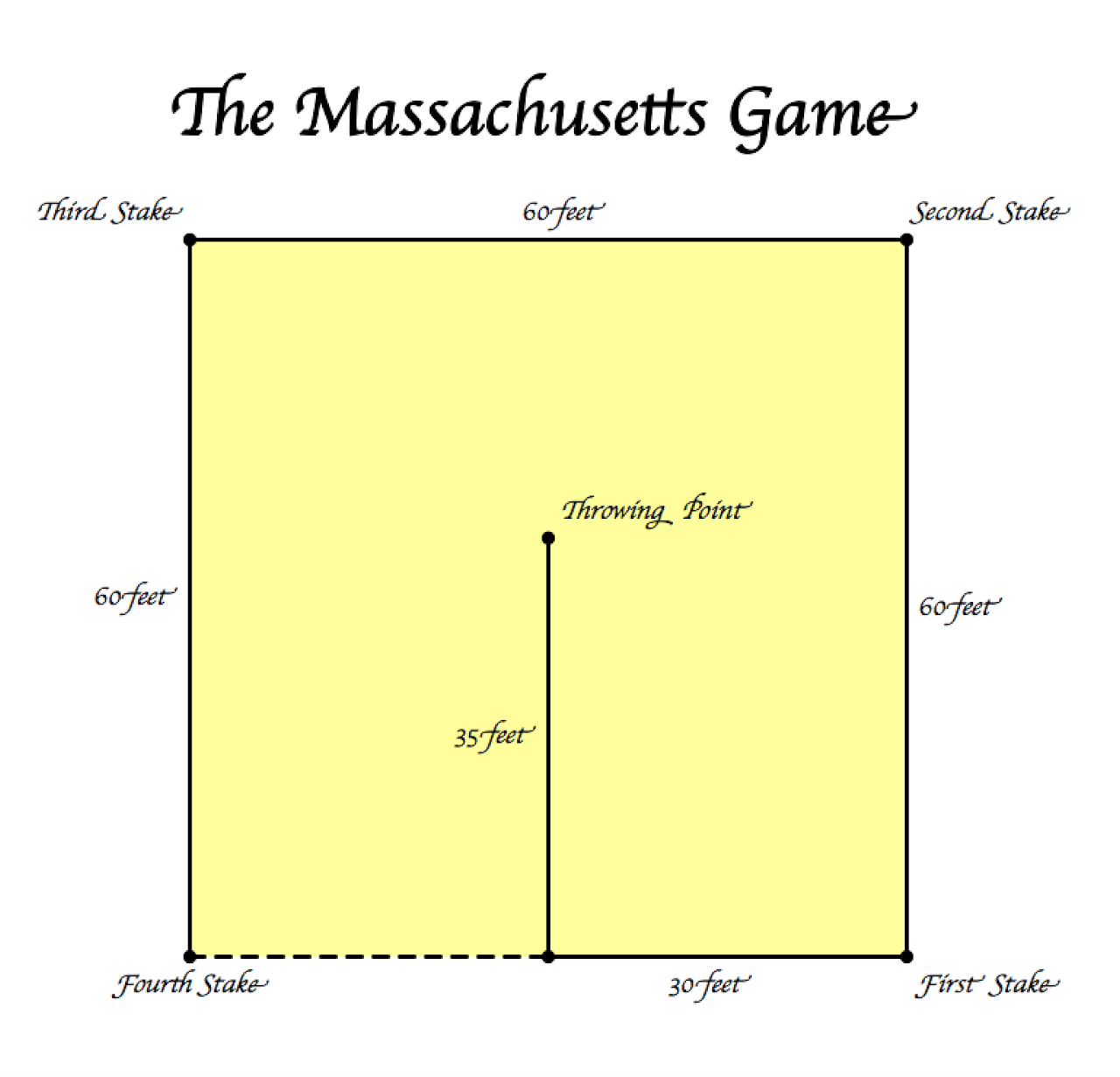

The Massachusetts Game in contrast lacks the same mathematical appeal and playability. Yes, as in baseball, the field of The Massachusetts Game is a square, but the batter’s box is located between the first and fourth stakes, facing the center of the square. This not only makes for an awkward lack of balance regarding the respective distances between the bases (see image below), but with first being only thirty feet from the batting point, and second sixty feet from first, this puts the pitching distance at a mere thirty-five feet from the batter. With a pitcher throwing swiftly, as is done in baseball today, this hardly makes for a fair contest between the pitcher and the batter (Ironically, it should be noted that swift pitching was originally allowed in The Massachusetts Game but not in the New York Game. Click here for more information about this).

However, regardless of the geometric flaws, The Massachusetts Game still happens to be an extraordinarily playable game.

John Thorn, the official historian of Major League Baseball, agrees.

“I think the New York game won out through superior public relations because I have played recreation games of the Massachusetts game and it is a fantastically fun game both to play and watch. The New York game, in many measures, is inferior. [In the Massachusetts game] you did not have to stay on the base path while you were running. So you could lead your opponents on a merry chase into the outfields and beyond.”

But with the dominance of The Knickerbockers over the bat-and-ball arena, together with the advantage of the mathematics being in their favor, once Boston’s Tri-Mountain Base Ball Club defected to the New York version in 1857, it wasn’t long before The Massachusetts Game was destined to become a mere footnote in the history of baseball in this Nation.

We here at Twenty-First Century Townball have aspired to revive the great game of Base Ball played in Massachusetts in the nineteenth century, but not in its original form.

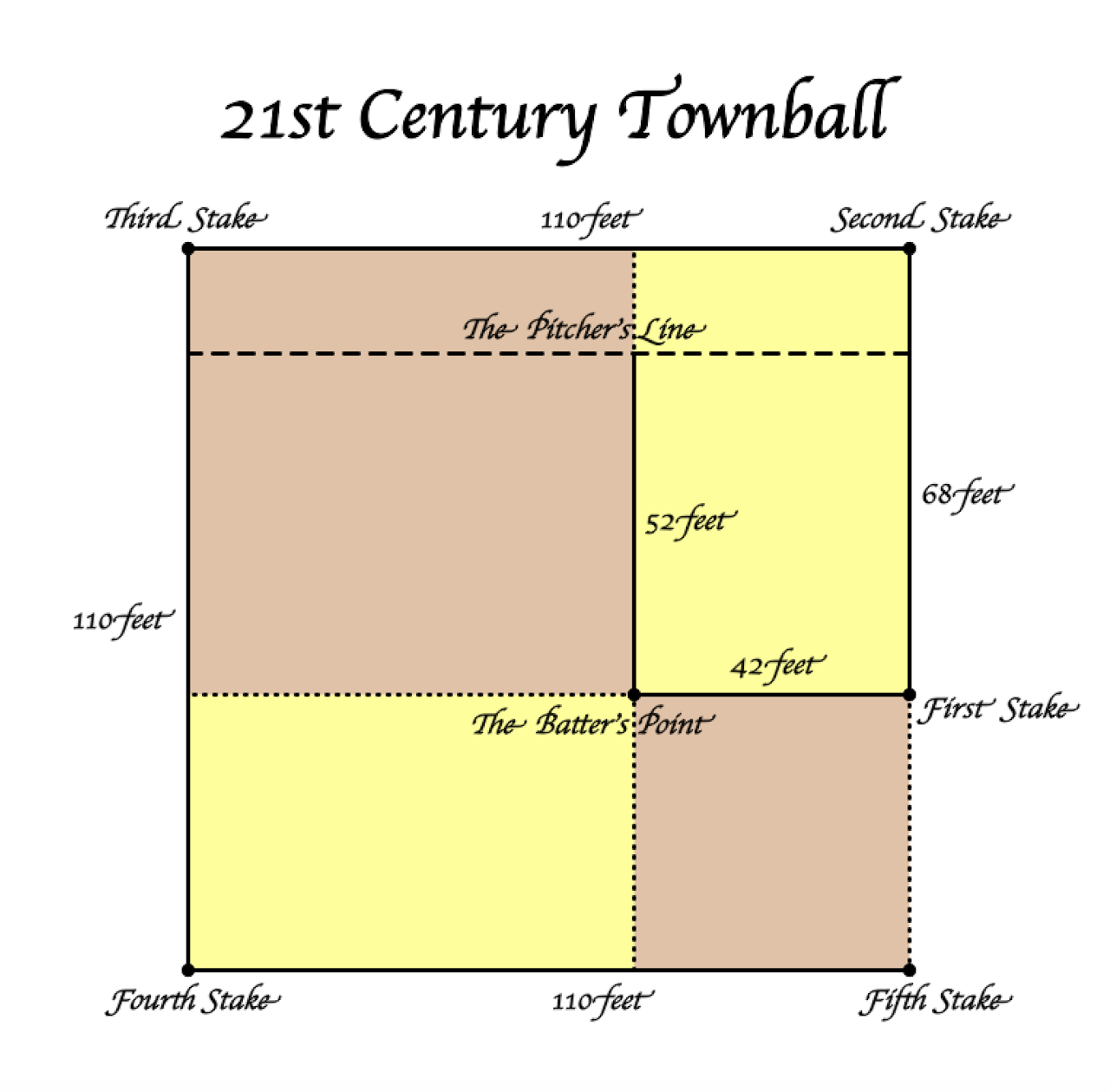

In Twenty-First Century Townball (see below), we have kept the square, but instead of batting from right between the first and fourth stakes, as is done in the original Massachusetts version, we started with a distance of 110 feet, and then cut the stakeline into the mean and extreme ratio, making first stake 42 feet from the batter. We then used the Fibonacci sequence to determine the remaining distances between each of the bases so that second is 68 feet from first, and the rest of the stakes are all 110 feet apart.

The fourth and final stake would have ended up on the batting and first stakeline if we were to keep to the original design, but we extended the distance between third and fourth to be equal to that between second and third, and then completed the square by adding a fifth stake back behind the batter in line with first and second.

The field now creates two “golden” rectangles and two squares within the infield. Thus Twenty-First Century Townball has a geometric appeal and playability at least equivalent to that of modern baseball.

And finally, in keeping with this theme of perfect mathematics in baseball, we have made every aspect of Twenty-First Century Townball in accord with the “golden” ratio.

To find out all the ways in which the ‘“golden” ratio is used in the creation of Twenty-First Century Townball, please read our next article, The Fibonacci Factor.